Principles for the Valuation of

Collective

Investment Schemes

Final Report

THE BOARD OF THE

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF SECURITIES COMMISSIONS

FR05/13 MAY 2013

ii

Copies of publications are available from:

The International Organization of Securities Commissions website www.iosco.org

© International Organization of Securities Commissions 2013. All rights reserved. Brief

excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated.

iii

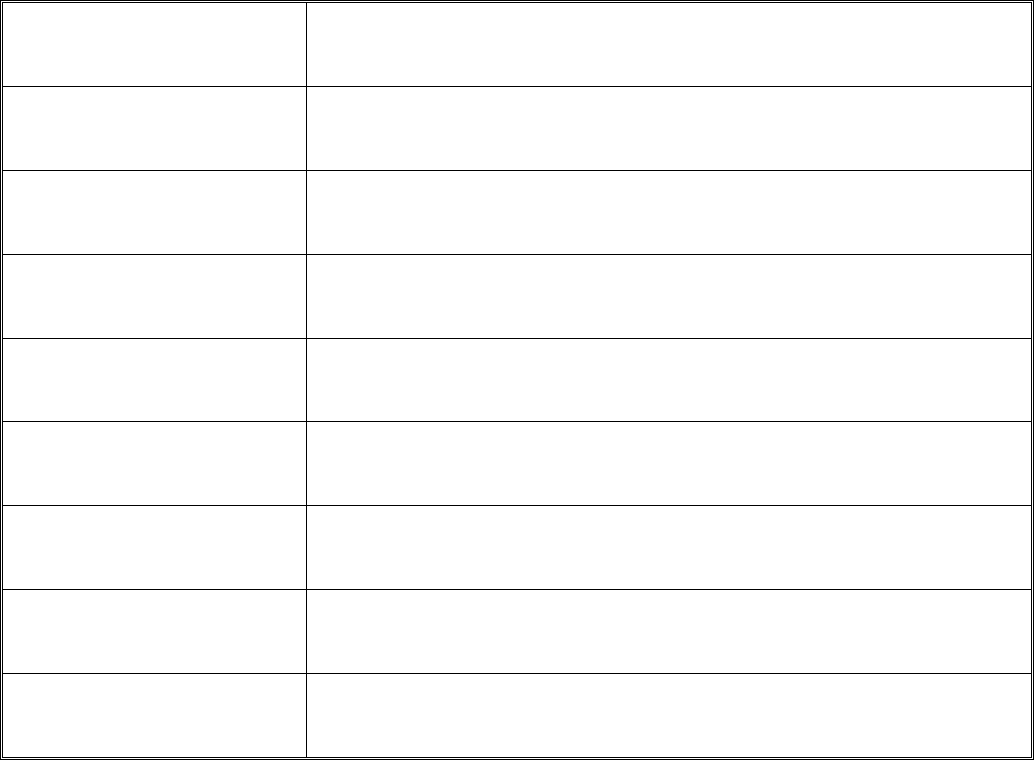

Contents

Chapter Page

Chapter 1 - Executive Summary 1

Chapter 2 – Introduction 3

Chapter 3 – Background 4

Chapter 4 – Principles for the valuation of collective investment schemes 5

Principle 1 5

Principle 2 5

Principle 3 6

Principle 4 7

Principle 5 8

Principle 6 9

Principle 7 10

Principle 8 10

Principle 9 10

Principle 10 11

Principle 11 11

Appendix A – Guiding Principles for the Valuation of CIS 12

Appendix B – Principles for the Valuation of Hedge Fund Portfolios 13

Appendix C – List of Principles for the Valuation of CIS 14

Appendix D - Feedback Statement on the Public Comments received on the Consultation

Report - Principles for the Valuation of Collective Investment Schemes 125

Appendix E - List of Working Group Members 27

1

Chapter 1 - Executive Summary

It is critical that a collective investment scheme (CIS) properly value all assets in its portfolio,

including those instruments for which market quotations are not readily available (e.g.,

restricted securities and many derivatives). Valuation is extremely important because a CIS

must redeem and sell its shares at their net asset value (the value of its portfolio securities and

other assets, less liabilities).

1

If CIS portfolio securities and assets are incorrectly valued, CIS

investors may unfairly pay more for their shares (or unfairly receive less upon redemption),

and investors remaining in the CIS also may be adversely affected.

IOSCO previously examined CIS valuation in the 1999 report, Regulatory Approaches to the

Valuation and Pricing of Collective Investment Schemes

2

(Valuation Paper). The Valuation

Paper listed several guiding principles for the pricing of CIS interests and valuation of CIS

portfolios.

3

In 2007, IOSCO also published Principles for the Valuation of Hedge Fund

Portfolios.

4

That paper identified nine principles designed to ensure that a hedge fund’s

financial instruments are appropriately valued and, in particular, that these values are not

distorted to the disadvantage of fund investors.

5

In addition, IOSCO’s Committee 5 on

Investment Management (C5) has also examined related topics.

6

There have been a number of developments that have impacted valuation since IOSCO last

reviewed CIS valuation. Many complex and hard-to-value assets are now available to CIS,

including some that did not exist a decade ago (such as certain structured financial instruments

and OTC derivatives).

7

The value of such assets cannot be determined by using quoted

prices (so- called mark-to-market), but instead CIS may rely on internal techniques which

imply management’s judgment (so-called mark-to-model). The difficulty and subjectivity of

1

Principle 27 of the IOSCO objectives and principles of securities regulation states that: “Regulation

should ensure that there is a proper and disclosed basis for asset valuation and the pricing and the

redemption of units in a collective investment scheme.”

See IOSCO Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation, IOSCO Report, 10 June 2010, available at

http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD323.pdf.

2

See Regulatory Approaches to the Valuation and Pricing of Collective Investment Schemes, IOSCO

Report, May 1999, available at http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD91.pdf.

3

Ibid. The guiding principles are attached at appendix A.

4

See Principles for the Valuation of Hedge Fund Portfolios, IOSCO Report, November 2007, available

at http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD253.pdf.

5

Ibid. These principles are attached at appendix B.

6

See FR02/12 Principles on Suspensions of Redemptions in Collective Investment Schemes, Final

Report, 19 January 2012, available at http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD367.pdf.

and

Principles of Liquidity Risk Management in Collective Investment Schemes, Final Report, 4 March 2013,

available at

http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD405.pdf

7

The term assets as used in this paper refers to all of the assets in a CIS’s portfolio. For example, assets

include, but are not limited to, equity and fixed income securities, positions in derivatives, and short

positions.

2

valuation increases regulatory risks and requires general principles to be supplemented by the

identification of policies and procedures designed to address the appropriate valuation of CIS

assets. This paper seeks to update and modernize principles for CIS valuation, taking into

account the prior work and recent market developments that impact valuation.

In preparing these principles, IOSCO considered comments received in the consultation

process.

8

The principles outlined are intended to be a basis against which both the industry

and regulators can assess the quality of regulation and industry practices concerning CIS

valuation. Generally, these principles reflect a level of common approach and are a practical

guide for regulators and industry practitioners. Implementation of the principles may vary

from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, depending on local conditions and circumstances.

8

See Principles for the Valuation of Collective Investment Schemes, IOSCO Consultation Report, Feb.

2012, available at: http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD370.pdf

.

3

Chapter 2 – Introduction

IOSCO’s Committee on Investment Management (C5) drafted this paper following a mandate

from the IOSCO Board. This mandate requested that it update collective investment scheme

(CIS) valuation principles with a major focus on policies and procedures related to the

valuation process in order to ensure that CIS asset valuations are not distorted to the

disadvantage of CIS investors. In the context of such work, the term CIS refers to those

collective investment schemes that are open-ended and provide regular redemptions to

shareholders at net asset value (the then-current value of their portfolio securities and other

assets, less liabilities) (NAV).

9

This paper identifies the implementation of comprehensive policies and procedures for

valuation of CIS assets as a central principle. It recommends general principles that should

apply to the development and implementation of such policies and procedures. The paper

also emphasizes that these policies and procedures should be consistently applied. In addition,

it stresses the goals of independent oversight in the establishment and application of the policies

and procedures in order to mitigate the conflicts of interests that CIS operators face. The key

objective underlying the CIS valuation principles outlined below is that investors should be

treated fairly.

9

In the context of this paper, CIS does not include a CIS for which the applicable jurisdiction regulates the

CIS operator, but does not impose valuation requirements at the level of the CIS. The principles outlined

in this paper may serve as best practices for such CIS, as applicable.

4

Chapter 3 – Background

The valuation of the assets employed or held by a CIS is critical to investors because it

affects, among other things, the CIS’s NAV, financial reporting, performance reporting and

presentation, and fees paid to CIS service providers (such as the CIS operator). Therefore, it is

crucial to understand all the valuation drivers in order to reach a correct valuation of the assets

in the portfolio or, before purchasing/selling an asset, in order to assess the correct value of

such an asset.

The valuation of CIS assets potentially presents conflicts between the interests of those who

value the assets and the CIS investors. There are many different ways in which this could

occur. For example, a CIS operator or other conflicted entity could overvalue the CIS assets in

an attempt to attract more investors by showing an inflated performance record, therefore

earning more management fees. In addition, a CIS operator could dump unattractive assets

that it or an affiliate owns by placing them into the CIS at an overvalued price. The CIS

operator could also undervalue the CIS’s assets and cause the CIS to sell them to affiliates at an

artificially low price. Therefore, the management of conflicts of interests is critical to ensuring

that the CIS’s assets are valued properly, and that CIS investors are protected.

The CIS governance framework in the jurisdictions of C5 members, including how the

framework addresses conflicts of interests, will reflect the legal structure of CIS in the

jurisdictions. For more information, please refer to IOSCO’s previous examination of CIS

governance framework and attendant conflicts of interest in the paper, Examination of

Governance for Collective Investment Schemes

10

published in February 2005. Throughout

this paper, the entity or entities responsible for the overall operation of the CIS and, in

particular, its compliance with the legal and regulatory framework in the respective jurisdiction

are referred to as the Responsible Entity.

11

10

See Examination of Governance for Collective Investment Schemes, Consultation Report, IOSCO Report,

February 2005 available at http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD183.pdf.

11

The identification of the “Responsible Entity” may vary among jurisdictions and types of CIS. In some

jurisdictions, the Responsible Entity could be the management company or the CIS itself. In others, the

management company may play a role in carrying out the principles, but may be overseen by an

independent body (e.g. board of directors).

5

Chapter 4 – Principles for the valuation of collective investment schemes

Principle 1: The Responsible Entity should establish comprehensive, documented policies

and procedures to govern the valuation of assets held or employed by a CIS.

While the CIS portfolio manager may be heavily involved in formulating the policies and

procedures, the Responsible Entity should ensure that written policies, and procedures which

implement the policies, are established and implemented to seek to ensure integrity in the

valuation process.

Principle 2: The policies and procedures should identify the methodologies that will be

used for valuing each type of asset held or employed by the CIS.

The CIS policies and procedures should set out the methodology to be used for valuing each

type of asset, which could include inputs, models and the selection criteria for pricing and

market data sources, having regard to sound and reliable data. The types of assets that a CIS

holds may vary according to the CIS’s investment objectives and applicable regulations.

12

Therefore, a CIS’s policies and procedures should be appropriate to the types and complexity

of assets that it holds and employs and in line with market conditions. For example, one CIS

may invest in assets that are traded frequently and for which prices are readily available and

reliable (such as on an exchange). In this case, the CIS’s methodologies for valuing these

assets may be relatively generalized.

Another CIS may invest in more complex assets that are more difficult to value (such as OTC

derivatives), and thereby may utilize particular methodologies relevant to those assets to

address those valuation issues. In these cases, it may be appropriate to consider whether the

valuations of the more complex assets requires specific skills and systems; in particular,

whether the personnel in charge of the valuation should have an appropriate level of

knowledge, experience and training.

While each jurisdiction may have different rules and guidance for valuing particular types of

assets, C5 has identified certain general practices that may be useful in considering the

appropriate methodologies for valuing CIS assets. First and most importantly, valuations

should be determined in good faith.

13

Where possible, assets should be valued according to

current market prices, providing that those prices are available, reliable, and frequently

updated.

12

In addition, jurisdictions may have different requirements for CIS that invest in certain asset classes (e.g.,

in some jurisdictions, an independent assessor is required to value real estate CIS). Such CIS may be

required to value its assets less frequently than other types of CIS.

13

See Principle 1 in Regulatory Approaches to the Valuation and Pricing of Collective Investment

Schemes, IOSCO, May 1999, supra fn 2.

6

However, there may be circumstances where it may be more appropriate to value the asset

using appropriate valuation techniques if the use of the most recent market price is not

appropriate, such as in the case of a security that has not traded frequently, or is otherwise

illiquid and hard-to-value.

14

As stated above, the CIS also should consider whether specific

skills and systems are necessary in considering valuation issues regarding hard-to-value

assets.

15

Frequently, hard-to-value assets tend to be illiquid (with a very limited or no secondary

market). In this respect, a CIS portfolio manager should monitor the liquidity in markets in

which the CIS is invested as part of a liquidity management policy. The more illiquid such

markets are, the more robust the valuation process may need to be. Similarly, as part of risk

management, where appropriate to the applicable jurisdiction and CIS, the policies and

procedures could consider valuation practices in normal and stressed market conditions.

When taking into account the opinion of a third party (e.g., a valuation agent or an external

rating), the Responsible Entity should assess the methodology and parameters on which such

opinion was produced in considering whether the opinion is suitable.

Principle 3: The valuation policies and procedures should seek to address conflicts of

interest.

Potential conflicts of interest regarding valuation of a CIS’s portfolio assets can arise in a

number of ways. For example, while the Responsible Entity remains ultimately responsible

for overseeing the implementation of the CIS’s valuation policies and procedures, in some

cases the CIS operator can have input into the appropriateness of a particular valuation. For

example, in cases involving complex or illiquid assets that are hard to value, the CIS operator

may in practice be the most reliable or only source of information about pricing for a particular

asset. However, the CIS operator has a conflict of interest with regard to the CIS’s valuations,

particularly as its fees are calculated based on the CIS’s assets under management. As a result,

the CIS operator has an incentive to overvalue CIS assets to increase its fees.

Conflicts of interest can be addressed in a number of ways. For example, reviews of valuations

that are independent of the CIS operator can help to ensure that the valuations of assets have

been determined fairly and in good faith, and protect investors as CIS must redeem and

14

For example, in some jurisdictions, certain securitized and structured finance instruments (SFIs) are

considered as hard-to-value assets. In these jurisdictions, in valuing such assets (such as

collateralized debt obligations, residential mortgage-backed securities and other types of asset backed

securities), marking the SFI to model implies an appropriate analysis of its underlying assets and

structure, including collateral. IOSCO previously examined good practices for investment managers

when investing in SFI see Good Practices in Relation to Investment Managers’ Due Diligence When

Investing in Str

uctured F

inancial Instruments, Final Report, IOSCO Report, 29 July 2009, available at:

htt

p://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD300.pdf.

15

For example, an appropriate valuation technique could include, if consistent with the applicable

jurisdiction’s regulations, valuing the asset using a marking-to-model technique that takes into account all

of the relevant information, including market data. For CIS that use models, the policies and procedures

should consider how to update the model over time.

7

sell their shares at NAV. In order to meet this objective, the following approaches would be

possible:

• A review of the valuation provided by the CIS operator that is hierarchically and

functionally independent of the CIS portfolio management function. Similarly, an

internal auditor or committee that is separate from the CIS portfolio management

function could review the valuations.

• Separate the valuation and/or pricing function, and thus not permit the CIS operator or

portfolio manager to determine the valuations, although the CIS operator may be able

to provide input, as appropriate. In addition, automating the valuation process to

reduce the possibility of human error, where possible, can help to reduce the possibility

of improper influence on valuations.

• Use of a CIS depositary, as applicable, to seek to ensure that the CIS operator carries

out the valuation of the CIS appropriately, therefore providing an independent check on

the valuation policy and the way it is implemented.

• A conflict of interests policy defined, implemented and maintained by the Responsible

Entity designed to manage conflicts associated with the valuation process, among other

things.

• An independent pricing service or other experts to assist the CIS in obtaining

independent valuations, as appropriate.

• If the valuation is obtained from a third party that itself has a conflict of interest (i.e.,

the counterparty of an OTC derivative, the structurer or the originator), verification of

an appropriate degree of objectivity in the valuation by one of the following:

o An appropriate party which is independent from the third party, at an adequate

frequency and in such a way that the Responsible Entity is able to check it;

o The depositary of the CIS; or

o A unit within the CIS which is independent from the department in charge of

managing the assets and which is adequately equipped for such purpose.

Principle 4: The assets held or employed by CIS should be consistently valued according

to the policies and procedures.

A CIS’s policies and procedures should make clear that the CIS’s assets are to be valued

consistently in accordance with the designated methodologies. In addition, the policies

should also generally be consistent across similar types of assets (e.g., assets that share similar

economic characteristics) and across all CIS that have the same CIS operator.

8

In certain exceptional circumstances, the value of an asset determined in accordance with the

CIS’s policies and procedures may not be appropriate. Therefore, it may be appropriate to

deviate from the methodology set forth in the policies and procedures and to determine the

value of the asset by using a different methodology, when, for example, the original

methodology does not result in the fair treatment of investors.

16

A price override (or deviation) is the rejection of a value for an asset that was determined

according to the established policies and procedures of the CIS. For example, price

overrides may occur where a pricing service or other third party is responsible for valuing an

asset, yet this valuation has been determined to be inappropriate.

The policies and procedures should describe the process for handling and documenting such

exceptional events, including:

(i) Documenting the reason for the price override;

(ii) Ensuring an appropriate review of price overrides by an independent party; and

(iii) Describing the method for determining the appropriate price.

Principle 5: A Responsible Entity should have policies and procedures in place that seek

to detect, prevent, and correct pricing errors. Pricing errors that result in a

material harm to CIS investors should be addressed promptly, and investors

fully compensated.

A pricing error occurs when a CIS’s price per unit is incorrect (i.e., the price is not an accurate

result of the CIS’s valuation process). A pricing error can result in an investor purchasing or

redeeming shares at the incorrect price. As stated above, an incorrect price could also

potentially affect the CIS’s payments to its service providers and to the CIS operator, among

other things.

Pricing errors can occur for a number of reasons. For example, incorrect accrual of CIS fees,

late reporting of trades in assets, or simple human error in inputting data can all produce pricing

errors. Accordingly, a Responsible Entity should have policies and procedures in place that

seek to detect and prevent pricing errors. The CIS policies and procedures should also identify

those pricing errors that materially harm investors, as determined by the appropriate

jurisdiction’s guidance, determination, or rules as appropriate.

For material pricing errors, investors should be compensated fully for the amount of the pricing

error in a manner that would correct the error, or otherwise in accordance with the applicable

16

In general, the valuation policies and procedures should specify a framework applicable to both current

and, where practicable, future assets in which the CIS anticipates investing. To this end, the valuation

policies and procedures should address how the valuation of assets will be undertaken in case an asset

falls outside of the scope of the existing valuation policy.

9

jurisdiction’s guidance or rules. Frequent pricing errors, or an escalation in the number of

pricing errors whether or not material, should prompt a review and amendment of the CIS’s

policies and procedures, as appropriate, to reduce or eliminate the number of pricing

errors.

Principle 6: The Responsible Entity should provide for the periodic review of the valuation

policies and procedures to seek to ensure their continued appropriateness

and effective implementation. A third party should review the CIS valuation

process at least annually.

The desirability of consistent application over time of the policies and procedures should be

balanced with a periodic review of, and appropriate changes to, the policies and procedures.

The policies should allow the Responsible Entity to review and change the methodologies

periodically and after any event that calls into question the validity or utility of the policies and

procedures (e.g. when market events call into question whether a particular pricing

methodology continues to be appropriate). This recognizes that CIS operate within a dynamic

environment in which the trading parameters, strategies and products change over time, and its

policies and procedures should be similarly dynamic.

As stated above, a CIS’s policies and procedures should make clear that the CIS’s assets are to

be valued consistently in accordance with the designated methodologies, among other things.

To this end, the CIS’s policies and procedures should be reviewed periodically to seek to ensure

that the policies and procedures continue to work as designed. For example, the review could

evaluate whether the valuations are consistent with designated methodologies and whether any

pricing overrides and errors are handled in accordance with the policies and procedures. The

review could also evaluate the CIS’s disaster recovery and business continuity policies and

procedures to ensure that the valuation process is able to be carried out in the event of an

emergency or other service disruption. This review should be performed by an entity or person

that is sufficiently independent of the valuation process such that an objective review can be

performed.

A CIS should arrange for a third party (e.g., an independent or external auditor as part of its

periodic review of a CIS’s financial statements,

17

depositary, custodian or accountant) to

perform an annual review of its valuation process. This review could be more frequent. A

third party can provide an independent review of the CIS valuation process, as relevant to the

particular jurisdictions’ regulations. In particular, a third party can verify the consistency of

the CIS’s NAV calculations and test the valuation procedures by which the CIS values its

assets.

17

In some jurisdictions, the audit must be conducted in accordance with internationally recognized

standards (e.g. GAAP or IFRS).

10

Principle 7: The Responsible Entity should conduct initial and periodic due diligence on

third parties that are appointed to perform valuation services.

The Responsible Entity typically appoints third parties to perform valuation services for the

CIS. Such third parties could include, among others, a valuation agent. If the Responsible

Entity decides to appoint a third party, suitable due diligence should be conducted by the

Responsible Entity to determine that the service provider has and maintains appropriate

systems, controls, and valuation policies and procedures, as well as a sufficient complement

of personnel with an appropriate level of knowledge, experience and training commensurate

with the CIS’s valuation needs. In addition, if valuation functions are delegated to a third

party, the third party’s activities must be periodically reviewed. Notwithstanding the use of a

third party, the Responsible Entity retains responsibility and liability for the valuations of the

CIS’s assets.

Principle 8: The Responsible Entity should seek to ensure that arrangements in place

for the valuation of the assets in the CIS's portfolio are disclosed

appropriately to investors in the CIS offering documents or otherwise

made transparent to investors.

Disclosure to investors about the CIS’s valuation policies and procedures could include general

information about how assets are valued and how frequently they are valued. This information

should be updated and made available to investors when these valuation policies and

procedures materially change.

18

Principle 9: The purchase and redemption of CIS interests generally should not be

effected at historic NAV.

19

Forward pricing is generally understood to be the practice of effecting purchasing and

redemption of CIS interests at the next computed NAV after receipt of the order. Generally,

cut-off times (i.e., the time at which the NAV is calculated, and before the orders have to be

received) are established to provide that investors receive the correct NAV for their redemption

and purchase orders.

20

As a result, investors will not know the NAV per share at the time of

18

For example, in the U.S., a CIS prospectus must disclose that the price of CIS shares is based on the CIS’s

NAV and the methods used to value the CIS’s assets (e.g. market price, or amortized cost). For non-

money market CIS, this disclosure must include a brief explanation of the circumstances under which it

will use a price other than market price and the effects of using this price. The prospectus is updated

annually or more frequently, depending on whether its information has changed materially. Other

jurisdictions may require the CIS’s policy to include a specific section illustrating the criteria used to value

the CIS assets. This information is then made available to investors upon request. In addition, certain

valuation criteria are reported in the notes to the CIS/sub- CIS annual report.

19

Historical pricing may be acceptable in certain jurisdictions for particular CIS. In these cases, this

principle may not apply to those CIS for which the applicable jurisdiction has permitted the use of

historical pricing. Due consideration should nevertheless be given to risks related to late trading and

market timing

20

In some jurisdictions, a CIS may offer and sell shares only on specific days (dealing day). The CIS

will announce the deadline for such dealing days. In these circumstances, an investor will receive the

11

placing the order, and all investor orders will be treated the same (i.e., given the same NAV) if

the orders are received by the cut-off time in good order.

21

Forward pricing ensures that

incoming, continuing and outgoing investors are treated equitably such that purchases and

redemptions of CIS interests are effected in a non-discriminatory manner.

22

Historical

pricing is the pricing method whereby investors purchase or redeem units/shares based on the

last calculated NAV of the CIS. In general, historical pricing would most likely have to be

justified only if the risks of abusive trades by insiders and resulting dilution of CIS interests are

minimized.

23

Principle 10

: A CIS’s portfolio should be valued on any day that CIS units are

purchased or redeemed.

24

CIS investors should purchase or redeem units at prices that fairly reflect the value of the

CIS’s assets. If a CIS’s assets are not valued on any day that CIS units are purchased or

redeemed,

25

it is possible that investors could purchase or redeem units at too low or too high a

price, thus harming CIS investors, and potentially affecting the CIS’s payments to its service

providers and to the CIS operator, among other things.

Principle 11: A CIS’s NAV should be available to investors at no fee.

As previously stated, a CIS provides regular redemptions and sales to investors at the next

computed NAV after receipt of the orders. Therefore, it is important that a CIS’s NAV is

available to investors at no fee. In some jurisdictions, the CIS is not required to disclose or

publish its NAV on a regular basis directly to investors, but the price of a CIS is generally

available on a daily basis in financial publications and websites and may also be available on

the CIS’s or CIS operator’s website.

NAV for the applicable dealing day if the order is received in good order by the dealing day's deadline.

21

When an order is considered received by the CIS may vary according to operational requirements in

various jurisdictions. For example, in some jurisdictions, an order paid for by personal check will not be

considered received in good order until the check has cleared.

22

See Best Practice Standards on Anti Market Timing and Associated Issues for CIS, Final Report,

IOSCO Report, October 2005, available at

http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD207.pdf,

recommends the use of forward pricing: “Forward pricing could be used to reduce the attractiveness of

CIS to market timing funds. CIS operators should consider selling and redeeming on the basis of an

unknown/forward price only and combining the cut off time and NAV calculation time in a manner

so as to minimize any arbitrage possibility arising from the timing differences, as the price of the

unit would be unknown to the investor at the time of placing the request.”

23

See Regulatory Approaches to the Valuation and Pricing of Collective Investment Schemes, IOSCO,

May 1999, supra fn 2.

24

Jurisdictions may have different requirements for certain assets, such as real estate assets,for which the

valuation may be required less frequently.

25

In general, applicable regulations might not require a CIS’s portfolio to be valued on days when the

applicable jurisdiction’s stock exchange is closed, such as a holiday.

12

Appendix A – Guiding Principles for the Valuation of CIS

26

The following fundamental guiding principles for valuation of CIS and pricing of CIS interests

were published in 1999 based on a study of regulatory approaches. These principles were

found to transcend jurisdictional boundaries.

• Valuation to be determined in good faith;

• CIS to be valued on a per unit/share basis based on the CIS’s asset value, net of

allowable fees and expenses previously disclosed to investors, divided by the number

of outstanding units/shares;

• Incoming, continuing and outgoing investors to be treated equitably such that purchases

and redemptions of CIS interests are effected in a non-discriminatory manner;

• CIS to be valued at regular intervals appropriate to the nature of scheme property;

• CIS to be valued in accordance with its constitutive and offering documents;

• Valuation methods to be consistently applied (unless change is desirable in the interests

of investors);

• Valuation and pricing basis adopted to be disclosed to investors in the CIS offering

documents.

26

See Regulatory Approaches to the Valuation and Pricing of Collective Investment Schemes, IOSCO,

May 1999, supra fn 2.

13

Appendix B – Principles for the Valuation of Hedge Fund Portfolios

The following nine principles were identified in IOSCO’s final report on valuation of hedge

funds in 2007:

27

1. Comprehensive, documented policies and procedures should be established for the

valuation of financial instruments held or employed by a hedge fund.

2. The policies should identify the methodologies that will be used for valuing each type

of financial instrument held or employed by the hedge fund.

3. The financial instruments held or employed by hedge funds should be consistently

valued according to the policies and procedures.

4. The policies and procedures should be reviewed periodically to seek to ensure their

continued appropriateness.

5. The Governing Body should seek to ensure that an appropriately high level of

independence is brought to bear in the application of the policies and procedures and whenever

they are reviewed.

6. The policies and procedures should seek to ensure that an appropriate level of

independent review is undertaken of each individual valuation and in particular of any

valuation that is influenced by the Manager.

7. The policies and procedures should describe the process for handling and documenting

price overrides, including the review of price overrides by an Independent Party.

8. The Governing Body should conduct initial and periodic due diligence on third parties

that are appointed to perform valuation services.

9. The arrangements in place for the valuation of the hedge fund’s investment portfolio

should be transparent to investors.

27

See Principles for the Valuation of Hedge Fund Portfolios, Final Report, IOSCO, November 2007,supra

fn 4.

14

Appendix C – List of Principles for the Valuation of CIS

Principle 1: The Responsible Entity should establish comprehensive, documented policies

and procedures to govern the valuation of assets held or employed by a CIS.

Principle 2: The policies and procedures should identify the methodologies that will be

used for valuing each type of asset held or employed by the CIS.

Principle 3: The valuation policies and procedures should seek to address conflicts of

interest.

Principle 4: The assets held or employed by CIS should be consistently valued according

to the policies and procedures.

Principle 5: A Responsible Entity should have policies and procedures in place that seek

to detect, prevent, and correct pricing errors. Pricing errors that result in a

material harm to CIS investors should be addressed promptly, and investors

fully compensated.

Principle 6: The Responsible Entity should provide for the periodic review of the

valuation policies and procedures to seek to ensure their continued

appropriateness and effective implementation. A third party should review

the CIS valuation process at least annually.

Principle 7: The Responsible Entity should conduct initial and periodic due diligence on

third parties that are appointed to perform valuation services.

Principle 8: The Responsible Entity should seek to ensure that arrangements in place

for the valuation of the assets in the CIS's portfolio are disclosed

appropriately to investors in the CIS offering documents or otherwise

made transparent to investors.

Principle 9: The purchase and redemption of CIS interests generally should not be

effected at historic NAV.

Principle 10

: A CIS’s portfolio should be valued on any day that CIS units are

purchased or redeemed.

Principle 11: A CIS’s NAV should be available to investors at no fee.

15

Appendix D – Feedback Statement on the Public Comments received on the

Consultation Report - Principles for the Valuation of Collective Investment

Schemes

Eighteen responses were received in relation to the Consultation Report – Principles for the

Valuation of Collective Investment Schemes as published by IOSCO and put out for public

consultation from 16 February 2012 to 18 May 2012.

Non-confidential comments were submitted by the following organizations:

AFG

Association of Luxembourg Fund Industry (Alfi)

Amundi Asset Management (Amundi)

APG Asset Management (APG)

Christoph Barnard

BlackRock

Bundesverband Investment und Asset Management e.V. (BVI)

Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA)

Financial Superintendence of Colombia (SFC)

HSBC Bank (HSBC)

International Valuation Standards Council (IVSC)

Investment Management Association (IMA)

Irish Funds Industry Association (IFIA)

Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia (ICAA)

Investment Company Institute (ICI)

Markit

National Futures Association (NFA)

South Africa FSB (SAF)

16

IOSCO took these comments (and those submitted on a confidential basis) into account in

preparing the final report. This feedback statement summarizes the main issues raised in the

responses received and notes where any changes have been made to the report.

General Comments:

1. Overall, most respondents thought that the report adequately addressed how a CIS

should value its portfolio assets, although one respondent thought that the principles

focused too much on conflicts of interest to the exclusion of other risks (IVSC). Some

respondents believed that the report could go further in reflecting recent regulatory

changes (Alfi) or deal with specific issues such as when a CIS transacts with related

parties (ICAA).

2. Some respondents disagreed with the report’s examples of how a CIS could manage

conflicts of interest and thought that more stringent principles were necessary (DFSA,

IVSC). One respondent thought that the report adequately addressed these issues but

had specific recommendations, such as requiring that a CIS have a valuation committee

(IFIA).

3. A few respondents suggested that the report address areas such as intraday trading, CIS

liquidation, suspension of NAV, pricing vendors and third party licensing (Alfi, SAF,

SFC). One respondent suggested that the report include a discussion of the importance

of business continuity planning and disaster recovery (ICI).

4. Some respondents had questions and suggestions regarding some of the defined terms, in

particular “CIS” (NFA and Alfi) and “Responsible Entity” and how they related to other

IOSCO work and the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (IVSC,

BlackRock, IFIA).

Specific Comments:

Principle 1

(i) Some respondents asked that the report clarify that Responsible Entity may designate the

administrator and the CIS management company to perform certain valuation processes

(Amundi and HSBC).

• IOSCO believes that the wording is sufficiently flexible to permit such

designation, where permissible by the applicable jurisdiction.

17

(ii) Some respondents commented that the report should clarify that the Responsible Entity

(which may or may not be the CIS) should have responsibility for setting and

maintaining valuation policies and procedures (HSBC and IMA).

• IOSCO did not change the wording, as it provides that the Responsible Entity

should establish valuation policies and procedures. Principle 6 addresses the

review of the policies and procedures.

(iii) Please clarify in the text that the principles should be approved (IFIA).

• IOSCO believes that the principle’s wording, as drafted, would encompass any

necessary approvals.

(iv) The policies and procedures should be consistent across the industry in a jurisdiction to

enable proper monitoring and authorization of cross border dealings. (SAF)

• Given the diversity of CIS, jurisdictional requirements, and changing markets, all

of which make it difficult to require uniformity, IOSCO did not incorporate this

concept.

Principle 2.

(i) Some respondents believed that the principle should address the policies and procedures

for all of the assets in which a CIS may invest and provide more guidance on valuing

these assets (e.g., Global Investment Performance Standards 2010, IFRS/US GAAP and

the Basel II Accord) (ICAA, IFIA). Some also wanted more guidance on hard-to-value

assets (Markit and Alfi).

• The report is intended to outline general principles on which both the industry

and regulators can access the quality of regulation and industry practices

regarding CIS valuation. Therefore, it is beyond the scope of the report to

provide definitive technical guidance on valuation practices.

(ii) Some respondents requested that the principle or the report should clarify that the CIS

must list all of the assets in which it will invest, and also identify how these assets are

valued, the source of the valuation, and the materiality thresholds relative to the

valuation obtained from other 3

rd

party sources (ICAA, IFIA). On the other hand, some

respondents believe it is inappropriate for the report to discuss valuation

“methodologies” or to prescribe methods that are to be used to value CIS assets (IVSC).

18

• The report is intended to outline general principles on which both the industry

and regulators can access the quality of regulation and industry practices

regarding CIS valuation. IOSCO believes this is the appropriate scope for the

report.

(iii) A respondent suggested that the report clarify that a CIS can only “trade illiquid

securities” when the offering document allows, and that specific liquidity measures will

be established to either side pocket or restrict redemptions associated with such

investments during the CIS’s lifetime (IFIA). One respondent believed that the report

should be more specific on how liquidity is measured and disclosed (Markit).

• Liquidity measures are discussed in Suspension of Redemptions in Collective

Investment Schemes, Report of the Technical Committee of IOSCO, March 2011,

available at: http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD349.pdf

(iv) One respondent requested that the principle require that Responsible Entity have policies

and procedures to oversee valuations made by individual portfolio managers

(Blackrock).

• Principle 3 addresses conflicts of interest that may occur between the

Responsible Entity and other entities, which could include individual portfolio

managers.

(v) A few respondents believed that the following text should be clarified: “The

methodologies used to value SFIs should be based on qualitative and quantitative

analyses which have to be conducted both in normal and stress scenarios” (ICI and

IVSC).

• IOSCO has modified the text to clarify that these methodologies apply to

monitoring liquidity generally.

(vi) Two respondents raised a number of issues relating to third parties, including delegation

criteria, required policies and procedures, assumptions, valuation techniques, and

appropriate functions (Markit and IFIA).

• Issues relating to third parties may vary significantly depending on the

jurisdiction and type of CIS, and thus are beyond the report’s scope.

19

(vii) One respondent objected to the principle and report’s use of certain terms (e.g., complex

assets, fair value, and other terms). This respondent generally requested that the

principle and text be more precise (ISVC).

• The report endeavors to use the terms that are most generally understood. It is

not intended to substitute for valuation methodologies, but instead sets forth

general principles.

Principle 3.

(i) Some respondents believed that if a third party provided a valuation, it would be

inappropriate for certain entities (such as a depositor or an internal auditor) to verify the

valuation, noting that, among other things, the depositary and/or internal auditor may not

have the requisite skills to perform these verifications, and also may not be truly

independent (AFG, IVSC, IFIA, Alfi, DFSA).

• The principle’s text provides possible approaches to addressing conflicts of

interest, and does not mandate any approach in particular. Therefore, the

application of the principle will depend on the facts and circumstances of each

CIS and its relevant regulations.

(ii) One respondent commented that the valuation policies and procedures should also assess

the way in which valuations are obtained in order to more fully address conflicts of

interest (SFC).

• The principle’s text notes that a Responsible Entity could define and maintain a

conflicts of interest policy. The text is drafted flexibly so that the Responsible

Entity could tailor its policy as appropriate, which could include assessing the

way in which valuations are obtained.

(iii) Some respondents asked for more guidance on what factors would make a third party

independent, particularly in terms of pricing agents (DFSA, IVSC).

• For purposes of this report, it is impracticable to provide detailed guidance on

what factors would make a third party independent, given the facts and

circumstances nature of this analysis.

(iv) One respondent suggested that a CIS should be required to have a valuation committee

(IFIA).

20

• While a valuation committee is one way in which a CIS can address valuation

issues and is mentioned in the report, there may be other appropriate methods,

depending on the applicable jurisdiction’s requirements.

(v) One respondent suggested that the discussion regarding automating the valuation process

should clarify that such automation reduced the possibility of human error, where

possible (ICI). Similarly, another respondent believed that the automation discussion

should be revised to avoid an inference that automation reduced the potential for

conflicts of interest (IVSC).

• IOSCO agrees and has modified the discussion accordingly.

Principle 4.

(i) One respondent strongly disagreed with the principle. It believed that a CIS’s valuation

policies should not dictate the methods or techniques used (e.g., each valuation would be

different for each security and it would compromise the independent and objectivity of

the valuer) (IVSC).

• IOSCO believes that the principle, as drafted, does not mandate the methods or

techniques that a CIS should incorporate into its valuation policies and

procedures.

(ii) Respondents had comments about the discussion regarding price overrides. One thought

that the discussion should clarify that staff tasked with reviewing price overrides should

have the appropriate knowledge and expertise to carry out that function (Alfi). One

respondent asked that the documentation for a price override should be based on a

credible valuation model or market insight that was not part of the initial valuation

decision that produced the price override. In addition, a valuation committee should

approve the rationale. Finally, the respondent noted that price overrides should occur

only in exceptional circumstances (IFIA).

• The discussion regarding price overrides is intended to provide general

guidelines and practices, in keeping with the various jurisdictions’ applicable

requirements. Thus, it is IOSCO’s view that requiring specific practices goes

beyond the scope of the report.

21

Principle 5.

(i) Some respondents thought that the text did not adequately address the appropriate

measures which could be adopted to identify/detect and prevent pricing errors (DFSA,

ICAA, IMA).

• Given the variety of facts and circumstances that could produce pricing errors, it

is difficult to provide specific guidance that would address these facts and

circumstances.

(ii) A few respondents asked that the text provide examples of materiality thresholds for

different fund types and valuation frequencies to define pricing errors that result in

material harm to CIS investors (HSBC, SAF). One thought that the text should clarify

that the materiality of the pricing error must be assessed according to the investment

objective of the CIS. For example, “materiality” is not the same between a money

market fund and an equity fund (AFG, Amundi). One respondent believed that the text

should discuss the reporting requirements for material pricing errors, e.g., when and to

whom should the CIS report a material pricing error, and how should it be documented

(IFIA). Another believed that the CIS should also be required to notify the regulators of

material pricing errors, and all pricing errors that benefit the CIS operator at the

expenses of investors (Chris Barnard)

• As respondents indicate, materiality is not a static concept. Therefore, it is not

possible to provide definitive guidance on materiality in the context of this

report.

(iii) One respondent commented that special attention should be given to pricing errors that

benefit the CIS operator at the expense of investors, such that the investor was always

compensated if a pricing error occurred. The respondent noted that pricing errors can

affect all CIS investors, not just those purchasing or redeeming units at the incorrect

price. These errors may also adversely affect investors that continue to hold CIS shares

(Chris Barnard).

• IOSCO believes that the text, as drafted, contemplates these scenarios, by

requiring that a CIS have policies and procedures that seek to detect and prevent

pricing errors, and that identify those errors that materially harm investors.

(iv) One respondent disagreed that a CIS should “compensate fully investors,” believing that

this would harm current CIS investors. Instead, the text should be revised to make it

clear that the Responsible Entity (or, the third party where the CIS is the Responsible

22

Entity), should compensate the CIS itself, in the interests of ongoing investors, as well as

investors that have suffered as they invested or redeemed (IMA).

• IOSCO has revised the text to clarify that other entities may be the ones

responsible for compensating fully investors for material pricing errors.

Principle 6.

(i) One respondent commented that a CIS should not have valuation policies and

procedures that require particular methodologies be used (IVSC). Others thought that

pricing policies and procedures are necessary to ensure the accuracy of valuation

policies by specialized third party vendors used when there is no market price (such as

with prices provided by counterparties of OTC instruments), and that the Responsible

Entities must understand the impact of pricing models used by central clearinghouses for

centrally-cleared derivatives (BlackRock). One respondent thought that the text should

include the independent review and disclosure of material changes to valuation policies,

procedures and/or methodologies (ICAA). Finally, one respondent believed that it was

not clear whether the valuation policies and procedures should change prior to a CIS

investing in a new asset, how and by whom the periodic review should be performed,

and that model assumptions should be reviewed more frequently than the periodic

review of the valuation policies and procedures (IFIA).

• IOSCO believes that a CIS should have valuation policies and procedures that

are periodically reviewed. As the variety of responses indicate, it is

impracticable to mandate specific requirements for valuation policies and

procedures, or the substance of their periodic review. Therefore, the principle

and text are drafted flexibly to accommodate various business models and

jurisdictional requirements.

(ii) At least two respondents believed that principles 6-8 should be combined (BVI, DFSA).

• IOSCO agrees and has combined these principles.

Principle 7

(i) One respondent suggested requiring a minimum frequency for review (IVSC).

• The principle, as drafted, requires that the policies and procedures be reviewed,

at a minimum, annually.

23

Principle 8

(i) One respondent believed that principle 8 should clarify that a CIS auditor should ensure

that the NAV is compliant with the accounting principles that are detailed in the

valuation methodology of each asset (AFG). Others believed that requiring a third party

to review the CIS’s valuation would be inappropriate (APG, IVSC) or that the external

auditors of the CIS should not be permitted to perform the review because of

independence concerns (Amundi, IFIA).

• With respect to accounting principles, a discussion of the various requirements

relative to the applicable jurisdictions is beyond the scope of the report. With

respect to which entity should perform the review, the text is drafted flexibly to

encompass different jurisdictional requirements.

(ii) One respondent disagreed that the audit should be performed in accordance with GAAP

or IFRS (IVSC). A few respondents thought that the report should refer to the

independent verification made in accordance with ISAE 3402 and/or SSAE 16 (Alfi,

HSBC).

• The footnote to the text notes that some jurisdictions require that an audit be

conducted with GAAP or IFRS. Therefore, the footnote should not be read as

requiring that the audit be conducted with GAAP or IFRS where no such

jurisdictional requirement exists. Secondly, with respect to ISAE 3402 and/or

SSAE 16, the text notes that the review should be relevant to the particular

jurisdictions’ regulations.

(iii) One respondent asked that the text clarify that this review is performed using a sample

or risk-based approach rather than verifying all of the individual positions, and to note

that the providers of valuation services and NAV calculations are often different entities

(BlackRock).

• The text is intended to provide general guidance, and respondents should look to

the rules of their particular jurisdiction for whether a risk-based approach would

satisfy the annual review.

(iv) One respondent suggested that the results of the review should be communicated to the

regulator (SAF).

24

• It is IOSCO’s understanding that not all of the jurisdictions require that the

review of the valuation policies and procedures be communicated to the

regulator.

Principle 9.

(i) A few respondents suggested that the text clarify that the Responsible Entity, which

delegates the valuation, cannot in all cases retain the ability to perform the valuation

itself, but instead must always understand the process (AFG, IFIA). Others noted that

aspects of this principle are already covered under the IOSCO principles relating to

delegations (DFSA, IFIA (with respect to the AIFM Directive)). One respondent asked

that the text clarify that the asset management company may appoint an administrator

that computes NAV and an external valuation agent to assess the value of a particular

asset (Amundi).

• The report is not intended to alter existing jurisdictional requirements for

delegation. Thus, addressing specific facts and circumstances regarding the

appropriateness of delegation are beyond the scope of this report. IOSCO has

reworded the text to make it clearer that valuation functions may be delegated as

appropriate. IOSCO also reworded the last sentence to clarify that the

Responsible Entity retains responsibility and liability for the valuations of the

CIS’s assets, notwithstanding the use of a third party.

(ii) Several respondents had specific comments on the appropriate standards (e.g.,

independence) for various third parties, such as those that provide valuation services and

NAV calculation services, pure data vendors (which the respondent thought should not

be considered a third party under the principle), and whether appropriate certifications

should be required (BlackRock, BVI, ICAA, IVSC, Markit). One noted that in some

jurisdictions, the availability of valuation providers may be limited (SAF).

• The principle and text are written broadly to provide appropriate flexibility to

CIS and Responsible Entities, and does not require the use of a third party. As

stated above, IOSCO has revised the text to provide greater flexibility, given the

facts and circumstances involved and the various jurisdictional requirements.

(iii) One respondent asked that the report include a reference to the importance of disaster

recovery and business continuity planning in principle 1 and 9 (ICI).

25

• IOSCO revised the text to note that a third party review could include a review of

the CIS’s disaster recovery and business continuity planning with respect to the

valuation process.

Principle 10.

(i) A few respondents commented that the principle should consider other current

regulations and their disclosure requirements, such as the Key Information document

introduced by UCITS IV (Alfi, Amundi). On the other hand, one respondent believed

that current requirements under IOSCO principle 27 already cover this principle

(DFSA).

• The principle is written broadly to be consistent with various jurisdictions and

their disclosure requirements, as well as current IOSCO principles.

(ii) One respondent asked that the text clarify that the valuations are available to all

investors, whether or not investors request the information (e.g., on the CIS’s website)

(IFIA).

• IOSCO did not make the change, as some jurisdictions may not mandate that a

CIS have a website.

Principle 11.

(i) Respondents pointed to certain CIS, such as feeder funds and fund of funds, and noted

that they may have different cut offs than other investors (when the principle is that all

investor orders will be treated the same). The principle should provide that funds of

funds and feeder funds in practice price historically, although the underlying funds are

priced on a forward basis (Alfi, Amundi, SAF). Some also mentioned certain money

market CIS, which in some jurisdictions may use historical pricing to accommodate

clients who want to know what they pay as they buy (AFG, Amundi). Others also

mentioned certain concerns regarding historical pricing or practical concerns (APG,

DSA, AFG, IFIA).

• IOSCO has modified the text to reflect that historical pricing may be acceptable

in certain jurisdictions for particular CIS.

(ii) A few respondents thought that the principle should also discuss market timing and anti-

dilution techniques which may be employed by CIS (Alfi, Markit).

26

• As the text notes, market timing and anti-dilution techniques are addressed in

Best Practice Standards on Anti Market Timing and Associated Issues for CIS,

Final Report of the Technical Committee of OISCO, October 2005, available at:

http://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD207.pdf

Principle 12.

(i) One respondent believed that the principle was too restrictive. For example, one

respondent disagreed that CIS portfolio assets should be valued on any day on which

CIS assets are purchased or redeemed, with regard to open-ended funds in real estate or

other less liquid assets (BVI). Another believed that the requirement that a CIS be

valued on any day that its units are traded may not be consistent with market practice for

some fund types (Alfi). On the other hand, one respondent believed that the principle

should be more restrictive, particularly in light of accounting, management information,

risk management (compliance to exposure limits), etc. (SAF). One respondent asked that

the text clarify that there was a difference between NAV calculation and valuation

(Blackrock, IMA).

• IOSCO has revised the text to clarify that jurisdictions may have different

requirements for certain CIS, such as real estate CIS.

(ii) Respondents raised a number of other issues, such as: (i) addressing the balance between

disclosure to investors and understandability (with respect to hard-to-value assets) (Chris

Barnard); (ii) considering addressed excessive dealing/trading situations (HSBC); (iii)

considering including that the materiality of the estimated value of any assets for which

a valuation cannot be reliably determined on the valuation date should be considered, in

order to determine whether a reliable unit price may be calculated (ICAA); and (iv) the

principles should be more specific as to the exact timing of the valuation (Markit).

• These issues are beyond the scope of the principle, which is intended to provide

general guidance and provide sufficient flexibility to address different business

models and regulatory approaches.

Principle 13.

(i) One respondent suggested that the principle be reworded to suggest that a CIS’s NAV

should be available at no additional cost, because presumably the CIS’s NAV included

any such costs (Alfi). Another believed that there was a distinction between the CIS’s

NAV and its price, and that the principle should refer to a CIS’s price (IMA).

• IOSCO believes that the principle and text are sufficient as drafted.

27

Appendix E – List of Working Group Members

C5 Member jurisdiction

Organization

Italy

Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa (CONSOB)

- Co-Chair

United States of America

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) - Co-Chair

Brazil

Comissão de Valores Mobiliários Brazil (CVM)

France

Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF)

India

Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI)

Germany

Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFIN)

Portugal

Comissão do Mercado de Valores Mobiliários (CMVM)

United Kingdom

Financial Services Authority (FSA)